Memorial Day has become synonymous with the start of summer—picnics, beach sand, warm weather, shorts, sales—are the prevailing images that come to mind. There are usually a few op-ed pieces pointing out the meaning of the day and maybe a glimpse of a wreath laying ceremony at Arlington or at another military cemetery. Ho hum, pass the hot dogs. It wasn’t always that way.

With 600,000 dead after the Civil War memorializing the dead was a large part of life in the United States for the next few years. Decoration Day, now our Memorial Day, was conceived of as a day to decorate graves and remember the war dead. Gradually as time passed it became a day for parades and placing flags on Veterans graves. Mourning gave way to patriotism and nationalism.

In 1898, the country found itself once again at war—this time with Spain over Cuba. Cuba had been wracked with revolutions and civil discord for many years. The government had invented the concept of concentration camps and was breaking new ground in the oppression of its people. The many Americans who lived and worked in Cuba were being threatened and harassed. The newspapers of the day were clamoring for intervention and the annexation of the Spanish territories in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The government decided to send the USS Maine to protect American interests and perhaps to influence the situation.

The USS Maine was a large battleship commissioned in 1895 as part of a ship building push to match the ships being launched by Brazil and other South American countries. The ship sailed into Havana harbor in January 1898. The evening of February 15, 1898, the Maine blew up with a might roar. Over 260 sailors were killed in the inferno and the ship rapidly sank to the bottom of the harbor. The cause seemed to be an underwater mine floated up against the hull of the ship by the Spanish. The country was immediately up in arms and demanding vengeance.

“Remember the Maine. To Hell with Spain,” quickly became the rallying cry and with William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulizer’s New York World leading the charge, the country demanded war to avenge the Maine and toss the Spanish out of the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific. Young men quickly volunteered to serve and volunteer units were raised all over the country. (Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders are the best remembered.) Patriotic Americans all wanted to do something for the cause.

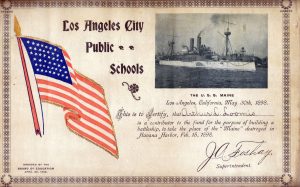

Given this atmosphere, the Los Angeles City Public Schools followed the lead of two Cincinnati school boys and started a children’s fundraising campaign. Students were encouraged to collect their change, and rob their piggy banks to contribute to a fund to rebuild the USS Maine. The new battleship was to be named The American Boy. Each child who made a donation received a certificate as proof of their contribution and patriotism. The certificate pictured is still in its patriotic frame decorated with small blue stars and was given to Santa Monica resident Arthur L. Loomis. As Arthur was only three years old at the time the donation no doubt came from his parents. In June the Los Angeles Times reported that the enthusiastic and patriotic students of Los Angeles had raised over $2,500 (over $65,000 in today’s money.)

The Spanish American War was a speedy affair. War was declared April 20th and the fighting ended August 12th. The peace treaty signed in December gave independence to Cuba and ceded Puerco Rico a December. The Maine was considered avenged and honored by numerous monuments in succeeding years. The mast of the ship was placed atop the mausoleum housing those killed in Arlington National Cemetery. A large monument still stands at the end of Central Park. Plaques made from the Maine’s armor plate were sent to cities who had contributed troops to the war. Other bits and pieces of the ship are scattered across the country. Veterans of the Spanish American War eventually became residents of the Soldier’s Home in West Los Angeles. The Civil War veterans called them “bamboos.”

A new USS Maine was built and commissioned in 1903; today the name is carried by a submarine. However, The American Boy was never built and the money collected seems to have been returned to the school districts or used to fund organizations that helped the families of the fallen. The Maine itself became one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the 20th century. Even after many investigations there is still no consensus as to what destroyed the Maine—a coal dust explosion, an underwater mine, or sabotage. Over a 100 years later, Puerto Rico and Guam are still American territories; the Philippines were given their independence after WW II; and Cuba remains a problem off the coast of Florida.